Dialog on Soul and Fate

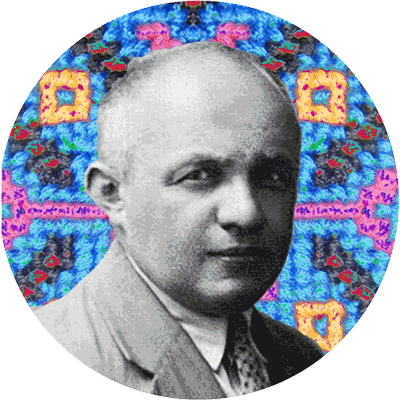

Stanislaw Vincenz (1888—1971)

BUDAPEST – NÓGRÁDVERŐCE (Hungary)

ABOUT EXHIBITION

Stanisław Vincenz at the end of secondary school, 1906

He was poor because he had lost everything that could be lost in this world. I guess he barely noticed it. He overcame poverty by limiting his needs to such an extent that any efforts to make living cheaper became unnecessary.

He was a Catholic believer and an unrepentant heretic. I do not think that there was anyone who believed in God more firmly, suffered from evil more severely, rebelled more intensely. He was inconsolable about the extermination of the Jews. I have never seen him speak of Jews except with tears in his eyes.

Jeanne Hersch, O Stanisławie Vincenzie [About Stanisław Vincenz], 1971

He was poor because he had lost everything that could be lost in this world. I guess he barely noticed it. He overcame poverty by limiting his needs to such an extent that any efforts to make living cheaper became unnecessary.

He was a Catholic believer and an unrepentant heretic. I do not think that there was anyone who believed in God more firmly, suffered from evil more severely, rebelled more intensely. He was inconsolable about the extermination of the Jews. I have never seen him speak of Jews except with tears in his eyes.

(Jeanne Hersch, O Stanisławie Vincenzie [About Stanisław Vincenz], 1971)

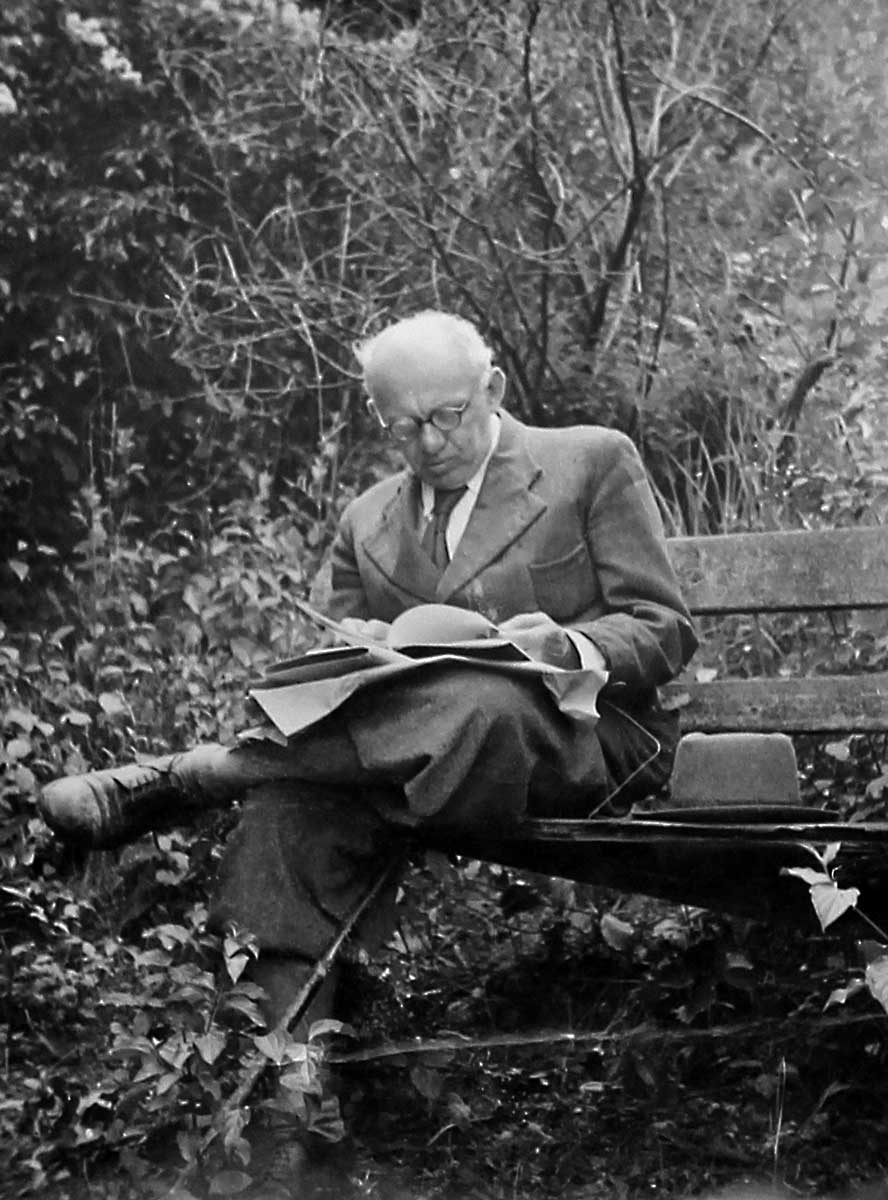

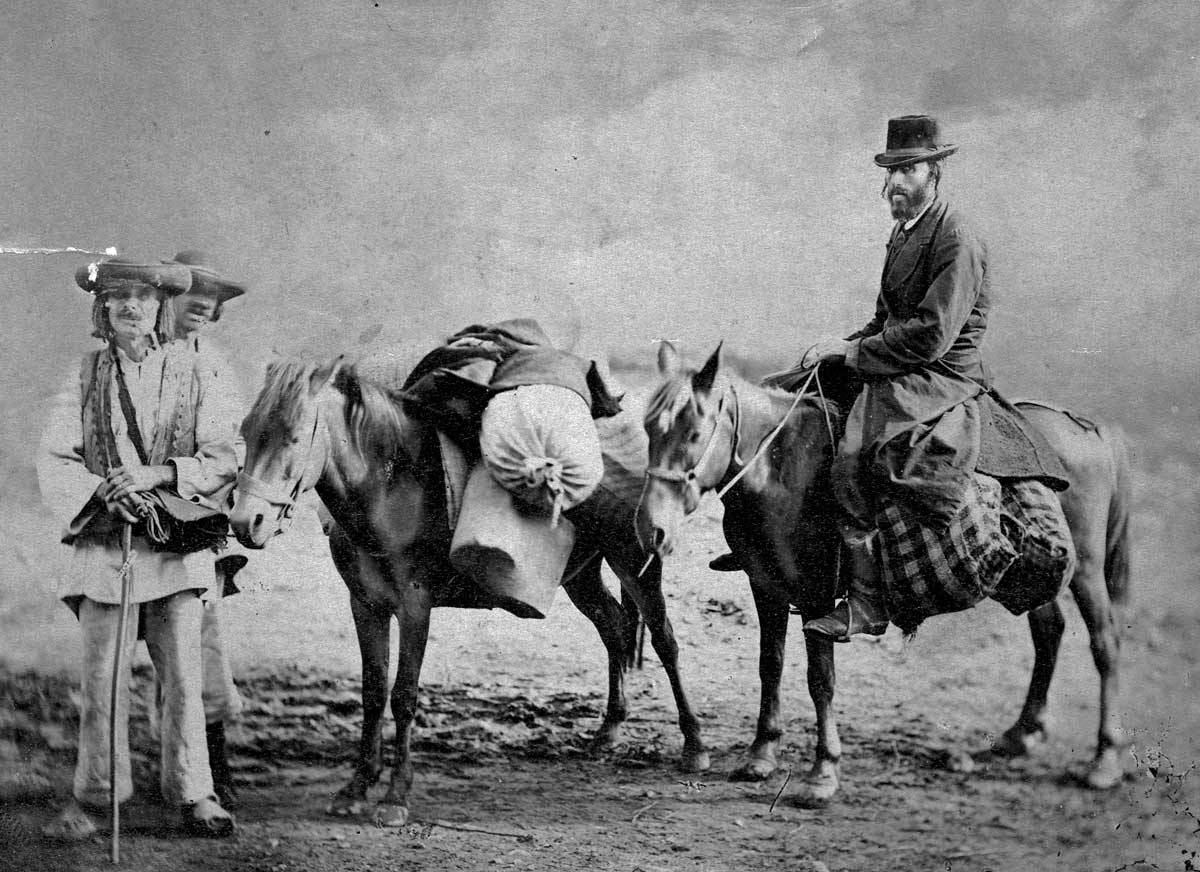

In Budapest with the Gertner brothers, 1942

Stanisław Vincenz as an officer of the Polish Army, 1920

I could not part and I will never part with the so-called Jagiellonian tradition. Namely, from the Karaims in the north to the Hutsuls and Hasidim, and historically, for example, from the Jesuits in Smolensk, the promotors of education in Moscow, to the Polish Arians, I came across their authentic remains in Hungary, all this for me is quite clear – it’s Poland.

(Stanisław Vincenz, a letter to Andrzej Bobkowski, 1954)

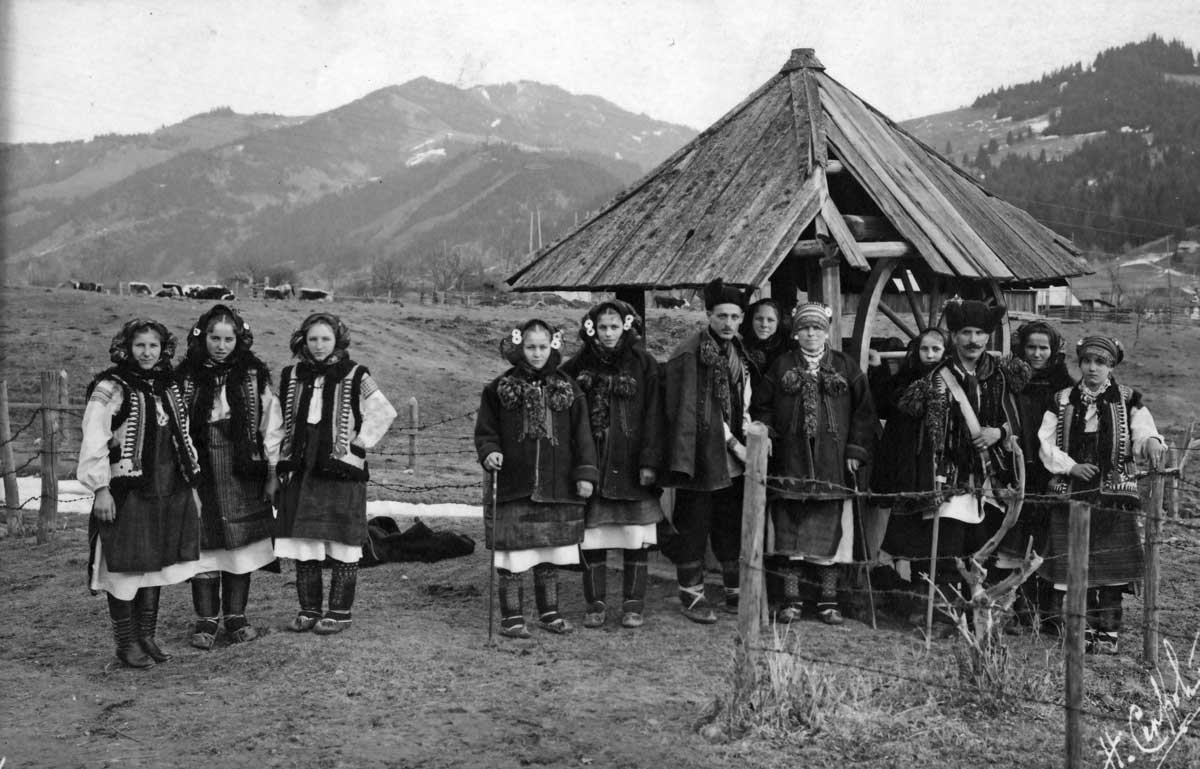

My song, similarly to the Czeremosz, collects all rivers, streams, brooks and creeks from the entire Wierchowina. And although we flow here in our own Czeremosz bed, although the river prevails over every tributary, it doesn’t disown any because it would almost dry up. It gives the waves its colour, it gives them its soil, shared depth, shared strength.

(Stanisław Vincenz, Barwinkowy wianek [A Periwinkle Garland], 1942)

A Hutsul is playing the trembita, 1933, photo by L. Cipriani

The thousand-year-old forest survived there until Stanisław Vincenz’s childhood. An almost unspoiled pastoral civilization of unprecedented antiquity has also been preserved. This land, which became part of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy after the fall of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, gave rise to many legendary characters. Two are the most famous: Dobosz and Rabin. Dobosz – the hetman of the highland robbers’ armies, robbed lords and merchants; he looked after the oppressed. It’s more than Janosik. Rabbi – Baal Shem Tov – would have been an ordinary innkeeper had it not been for the strength (the lamp in blood). He purged himself of the worldly attachments by living in a rock grotto and learning the language of birds, as well as getting to know living sparks hidden in a stone, plant, tree, he preached out of humility, out of the admiration for divine beauty in creation, and his teaching of love was followed both by Jews and Christians. And he had powers at his disposal. His students spread the teachings, and thus in Judaism a movement called Hasidism arose. There are homelands that keep mementos of their Napoleons, this one kept mementoes of the robber hetman and a gentle wiseman who followed the principles of the Sermon on the Mount. In Vincenz’s work, the fairy tale about them depicts two main themes, the pastoral civilization and Hasidism.

(Czesław Miłosz, La Combe, 1958)

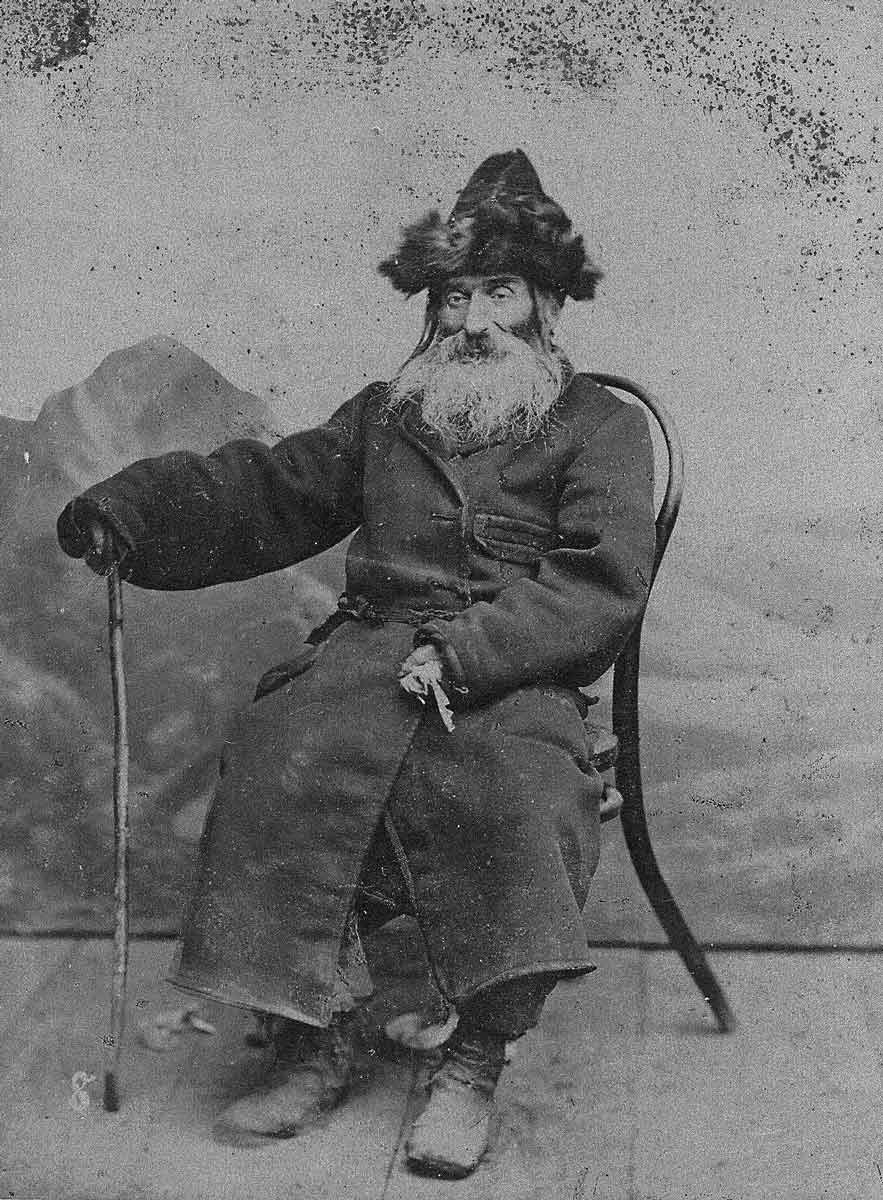

A Jew from Kołomyja, 19th century, photo by J. Dutkiewicz, the collection of PME

A Jew – tradesman from Żabi, 19th century, the collection of MEK

It was a long time ago – but it’s true. And this is a story over which many a wise head nodded. It was when the great Rabbi lived in Ostra.

The whole thing was that there was one little, quiet Jew in this Ostra. A tailor called Pinkas. Because Pinkas believed in the Rabbi, Pinkas consulted him constantly. He sometimes even made the Rabbi bored. But this was out of godly fear, so the great Rabbi was patient. He replied to Pinkas: Yes – no, no – yes. He did not raise his head from the book.

Every day Pinkas walked from his alley to the castle to the lord’s court and back. He went to sew at the Count’s court. Pinkas was just Count’s tailor. And this Count, like noblemen do, had relatives everywhere. Even the emperor, who then lived somewhere in Spain, was his relative.

And what is happening. The emperor once wrote to the Count:

“Dear Cousin, God is with you! I have a great request for you. The news is that you have a Jew with you, a real Jew! If that’s true then bring him with you and I will be very grateful to you. For me, for all my subjects, it is very important, it will be a great rarity. We have been short of Jews for a long time, and we just need him. You probably know that Jews are the greatest enemies of us Christians. And the holy faith commands us to love our enemies. But where to get them?”.

(Stanisław Vincenz, Rarytas [The Rarity], 1949)